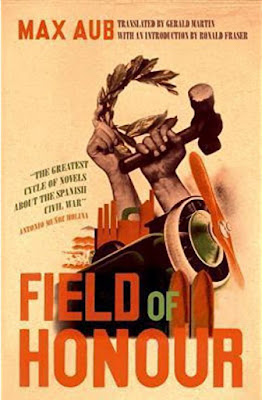

Field of Honour

Field of Honour was written by Max Aub in exile in Paris, May to

August 1939, and published in Mexico in 1943. Between the writing and the

publication – the author’s internment by the French and deportation to a

Concentration Camp in Algeria. Although a Spanish national, he was denounced as

a ‘German Jew’ and as ‘a notorious communist and active revolutionary’. More

could be said about the novel and its author: suppressed during the Franco

period, the novel did not receive its due attention in Spain

during the author’s life (he died in 1973). These facts I have gleaned from the book's introduction.

Field of Honour centres

on the life of one Rafael López Serrador, who grows up in the period between

the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, and the ill-fated Second Republic.

Serrador leaves his small town for Barcelona, where he finds work and then

education through a worker’s institute and his own wide-reading of everything

from Spanish poetry to Tolstoy. Much of the novel consists of recorded dialogue

as the young man mixes with different sides of the political spectrum: from

Communists, to Anarchists, to Reactionaries and the Falange. Seeking personal

freedom and perhaps swept up by an intellectual Falange-leader, Serrador seems

eventually to have found his cause – until the fighting breaks out in Barcelona

in the first days of the Spanish Civil War, and he is drawn back to the

Anarchists and their immediate passion for a new society.

This was an age of dichotomy and simplification. For

example, charismatic Falange-leader Luis Salomar thinks: ‘there were only

Spaniards and Arabs’ (p.111). He longs for Castilian Spain, in the days of

conquest and glory of empire. Preparing for the coming military coup, Serrador

waits in a garden with other young recruits, and Aub takes a moment to divert

the reader’s attention to the garden itself. He writes: ‘carnation beds with

neat little fences, pink coping everywhere; gleaming yellow corncobs and

crimson strings of dried peppers hanging down from the roof; tangled

bell-shaped vetch flowers following wire netting along the sun-blistered walls

…’ (p.161). It hardly seems the place for marksman practice, in other words,

and is nicely juxtaposed to the immediate violence and the shift to the action

of the coup and the tragedy that this unfolds on Spain over the protracted

civil war.

Field of Honour is the first of a six-novel epic, The Magic Labyrinth, and centres on the

events leading to Barcelona’s overthrow the military coup within the city in

1936. As such, we have a glimpse of hope and victory: ‘shivers of triumph run

through the city, cars and trucks full of workers, men and women, soldiers in

the air, cheering’ (p.230). The final chapter ‘Death’ lists the fate of the

various characters who have made up Serrador’s encounters in the years before

this temporary state of revolution within the coup: their deaths on the front

line, or by firing squad, or by various fates. Even had he not included this,

the dialogue about politics before the ‘action’ of the ending would have left

the reader with little hope of peace or utopia in Spain in this terrifying

period of history. For this and other reasons, the novel would appear to be one

that would inform any reader of the complexity of historical forces in an age

of turmoil in Spain and beyond. I read it in one sitting (broken up, I must

admit, by meals and sleep, as befits a holiday in France).

Comments

Post a Comment